I’m on the phone with Dr. Temple Grandin — best-selling author, famed animal behavior expert, high-functioning autistic and subject of the HBO biography drama Temple Grandin, which was nominated for 15 Emmy Awards. The topic of our discussion is, ostensibly, the Aug. 16, 2010, release of the film on DVD and Grandin’s involvement with the

movie’s production, which is based in part on two of her books, 1986’s Emergence: Labeled Autistic

movie’s production, which is based in part on two of her books, 1986’s Emergence: Labeled Autistic and 1996’s Thinking In Pictures and Other Reports From My Life With Autism

.

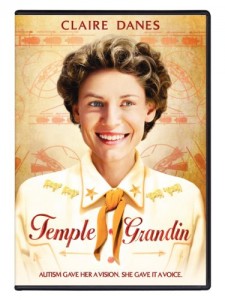

In HBO’s Temple Grandin, directed by Mick Jackson, Grandin is portrayed by Golden Globe-winner Claire DanesStardust).

“I thought Claire Danes did a fabulous job,” Grandin tells me.

I note that in the DVD commentary, Grandin says that Danes “really became me.” I ask her what it was like to witness an actress “becoming” her.

“It was like climbing into a weird time machine that let me see myself again as a teenager,” Grandin says, adding that she watched the filming on monitors rather than from the sidelines of the set itself, so as not to make Danes self-conscious by her presence.

Temple Grandin is arguably the Jane Goodall of her generation, although her research into animal behavior is focused a bit closer to home — concentrating on domestic pets and livestock. Over the past 20 years, Grandin has pioneered humane animal-handling equipment and practices that have been implemented by more than half of beef producers in the U.S. She has spoken and written extensively, in books such as 2004’s Animals in Translation and 2009’s Animals Make Us Human

, on the complex inner lives of dogs, cats, horses, cows, pigs, chickens and zoo animals.

“They exist because of us,” Grandin says. “That means we owe them respect.”

Because of her autism, Grandin’s perceptions of the world are different from most people’s — and these differences give her unique insights into the way animals think.

“I’m a visual thinker,” Grandin tells me. “I think in pictures, not words. Language is actually my second language.”

When Grandin hears the word “up,” for example, she doesn’t understand it in terms of the dictionary definition of the  word “up.” Instead, she sees a succession of images — of things like a ladder she climbed as a child, the stairs in her home, a sign with an arrow pointing upward, a plane taking off. The film depicts this process in a rapid-fire, flip-book fashion that Grandin says is a “completely accurate portrayal” of the way she thinks in real life. Because animals are also visual thinkers, as opposed to verbal thinkers (since they lack language), Grandin is able to understand their thought processes and anticipate their concerns and reactions in a way few other people can.

word “up.” Instead, she sees a succession of images — of things like a ladder she climbed as a child, the stairs in her home, a sign with an arrow pointing upward, a plane taking off. The film depicts this process in a rapid-fire, flip-book fashion that Grandin says is a “completely accurate portrayal” of the way she thinks in real life. Because animals are also visual thinkers, as opposed to verbal thinkers (since they lack language), Grandin is able to understand their thought processes and anticipate their concerns and reactions in a way few other people can.

“It was a long time before I realized not everybody thinks the way I do,” says Grandin. “I could never understand how people could be so apparently insensitive to an animal’s distress. Now I realize they just didn’t know.”

She notes that many of the people who seem to have the best rapport with animals are often autistics, dyslexics or people with other kinds of learning differences that lead them to think in images instead of words.

“The more verbal a person is, the less likely they are to be able to understand animals,” she says.

It’s at this point that I become concerned. I’m a writer, public speaker and former teenager with a 300-point gap between the verbal and math portions of my SAT scores. I’ve always thought of myself as a fundamentally verbal person. But I’ve also always thought of myself as a person who “understands” animals — in fact, just like being verbal,  being good with animals is one of the primary components of my self identity. My last book, Homer’s Odyssey: A Fearless Feline Tale, was written about my blind cat Homer and the incredible bond that has formed between us over the past 13 years. (Full disclosure: Temple Grandin was kind enough to blurb Homer’s Odyssey.) Yet it seems that what Grandin is saying is that I can’t be both verbal and sensitive to animals. It doesn’t take much to tip a writer into self-doubt, and I suddenly find myself wondering, What if I’m actually neither?

being good with animals is one of the primary components of my self identity. My last book, Homer’s Odyssey: A Fearless Feline Tale, was written about my blind cat Homer and the incredible bond that has formed between us over the past 13 years. (Full disclosure: Temple Grandin was kind enough to blurb Homer’s Odyssey.) Yet it seems that what Grandin is saying is that I can’t be both verbal and sensitive to animals. It doesn’t take much to tip a writer into self-doubt, and I suddenly find myself wondering, What if I’m actually neither?

I express this concern to Grandin. Hence the question about the boat. Grandin is going to give me a simple test to determine the extent to which I’m a visual thinker — if I am one at all.

“Think about a boat,” she says. “How does that come into your mind? Don’t think about it too much, just answer.”

“Okay,” I respond. “The first thing that comes into my mind is the marina where I first remember seeing boats as a child. It was at this place called The Castaways along A1A [in Hallandale, Florida, close to where I grew up], and it was on the way to my pediatrician’s office. It was a brown building with orange lettering, and they’d done it up to look like a  shack. The boats in the marina always seemed to be white or off-white, except for the cigarette boats — those were usually red.”

shack. The boats in the marina always seemed to be white or off-white, except for the cigarette boats — those were usually red.”

“Now, see, that’s very specific,” Grandin tells me. “Most people, if you say the word ‘boat’ to them, they think of the barest outline of something. They think of a stick figure. You’re a visual thinker.”

I feel strangely relieved, although I still can’t quite let go of the distinction she’s drawing between verbal and visual thinking.

“You think in pictures,” I say, “yet you have such a tremendous body of written work. Do you feel that in the process of converting your thoughts from images to words that things get lost in translation?”

“I work with a co-writer, and I have to be very disciplined when I’m writing and work from an outline,” Grandin tells me. “Visual thinkers tend to ramble when they write.”

I laugh. “I think that’s all writers.”

Grandin hasn’t laughed once during our conversation, but for the first time she sounds amused.

“Yes,” she agrees, “but especially the ones who are visual thinkers.”

Whew! I passed the boat test! Great interview, Gwen. I’ve watched this bio-pic a few times and I’ve enjoyed it; I’m glad Temple Grandin did too. It’s great that this talented woman’s views are getting more attention. Your interview does a great job clarifying Grandin’s pictoral view of animal understanding. Definitly provides another key piece in understanding my cats.

F*ckin? awesome issues here. I am very glad to peer your post. Thank you a lot and i’m looking ahead to touch you. Will you please drop me a mail?