Like so many others, when I first heard on Sunday, February 2nd of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death from a drug overdose, my sense of loss was immediate and personal. There was an instantaneous, visceral understanding—not of the loss of the Hoffman we had already seen and admired—but of the Hoffman we would never see over the course of half-a-lifetime’s worth of work still ahead of him. It’s been difficult for me to articulate that loss beyond my immediate lament of, “What a waste,” which I’ve found myself repeating with increasing frequency and sorrow as the days have passed and reflections on his work have piled up.

In 2009, I was fortunate enough to participate in a group interview with Philip Seymour Hoffman during the junket for Charlie Kaufman’s challenging and layered directorial debut, Synecdoche, New York, in which Hoffman starred. The interview/story, which originally appeared in Variety’s Video Business magazine, is re-printed in its entirety below.

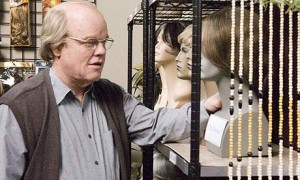

The Hoffman who sat down with the five of us—much like the Hoffman we know on-screen—seemed at first to be an un-prepossessing man, rumple-haired and dressed in shorts and a hoodie. Nobody who would turn heads or rivet attention if you didn’t already know who he was. But, within moments, he had captured the room with the quiet forcefulness of a supremely thoughtful and intelligent mind at work, only occasionally—and unapologetically—prickly when a question clearly failed to live up to the depth or seriousness he felt consideration of this particular film deserved.

At first glance, it would seem nothing short of astonishing that a man who neither possessed conventional good looks nor portrayed conventional heroes should rise to become not just a celebrated character actor, but a bona fide movie star who wielded considerable power off the screen while commanding rapturous love on it. And yet, upon further reflection, it really isn’t so surprising.

Most of us, when describing the unique bonds we have with the people we love most, are apt to say something like, “He gets me.” And Hoffman got us. He portrayed the unheroic, the misfitted, the neurotic and selfish and deeply flawed, and he did so perhaps not with great compassion or a desire to pardon, but in a manner that conveyed a more profound understanding and acceptance of the flaws that make us human than, arguably, any other actor working today. Hoffman didn’t go out of his way to make us feel better about ourselves, but he did go out of his way to let us know that he understood us. Sometimes understanding is all that’s needed to inspire love. Sometimes, the simple gift of letting us know that somebody “gets” us is the greatest gift an artist can give.

Today, we’re all short by one the small number of people in the world who truly understand us, who see all that’s occasionally ugly and small and worst in us and still embrace us anyway. We’ve lost an actor who would have spent the next several decades transmuting that ugliness into objects of painful, breathtaking beauty. We’ve lost someone who, in refusing to compromise in his artistic life, made it easier for the rest of us to live with the compromises we all make in our real lives. And we’ve lost the second half of a body of work that—amazing as it seems in the context of an actor who’d been working as long as Philip Seymour Hoffman—had only just entered its prime.

What a waste.

Video Business Magazine – February 23, 2009

Synecdoche the word means the representation of a whole by one of the parts. (Saying, “Let’s count heads,” for example, instead of, “Let’s count people.”) Synecdoche, New York, Charlie Kaufman’s directorial debut from his original screenplay, tells the story of Caden Cotard, a theater director whose wife has left him and whose own body has begun to turn against him as the result of a mysterious illness. Caden gathers an ensemble cast into a Manhattan warehouse in the hopes of creating a play of “brutal honesty.” He creates a miniature New York City within the enormous warehouse and casts actors in the roles of himself, his ex-wife, his daughter, his current love interest, and just about everyone he’s ever met or observed. As the cast swells, the city-within-a-city sprawls, and years of rehearsal roll by without a single performance, the lines between Caden’s artistic creation and his real life become increasingly–impossibly–blurred.

The complex, decades-spanning character of Caden Cotard is played by Philip Seymour Hoffman in a performance that’s at least as rich and nuanced as that of Father Brendan Flynn, Hoffman’s Oscar-nominated role in last year’s John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt.

“It’s about being forty, having children, being in a relationship. It’s about everyone,” Hoffman told VB in a recent interview. “It’s about life, about how everyone is a lead in their own story. It’s about how time moves fast, about growing old, about what children do to you.

“It’s not a movie to watch from a distance,” he adds. “If that’s what you’re doing, you’re kind of missing out.”

Kaufman’s exquisitely multi-layered narrative demands a lot from its actors, and Hoffman, who’s made his bones as perhaps the most versatile actor of his generation, seems ideally cast as Caden Cotard. When asked why he chose to accept the role in Kaufman’s film, Hoffman simply replies, “He asked me. I think he’s an extraordinary writer.”

Leave a Reply