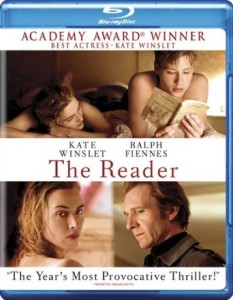

With last week’s publication of The Blue Touch Paper: A Memoir by the award-winning playwright, actor, director and screenwriter David Hare, I figured it would be a perfect time to dig up an interview I conducted several years back with Sir David. It was published in Video Business Magazine on the eve of the DVD and Blu-ray release of the Stephen Daldry-directed film The Reader, for which Hare penned the Oscar-nominated screenplay.

With last week’s publication of The Blue Touch Paper: A Memoir by the award-winning playwright, actor, director and screenwriter David Hare, I figured it would be a perfect time to dig up an interview I conducted several years back with Sir David. It was published in Video Business Magazine on the eve of the DVD and Blu-ray release of the Stephen Daldry-directed film The Reader, for which Hare penned the Oscar-nominated screenplay.

I enjoy interviewing members of the film and theater world’s creative community and I’ll admit I’m usually pretty light on my feet (and in my heart) while I’m at it. But with Hare, our lengthy phone discussion took on a more serious tone than usual, which is undoubtedly appropriate for a film such as The Reader.

Disc Dish: I’ve been reading interviews by you everywhere about The Reader.

Hare: Well, it was two years of my life.

DD: And you’re obviously very proud of it.

Hare: Both of the films I’ve made with Stephen Daldry—The Hours and The Reader—I’m very, very proud of. We put an awful lot of work into them and we were very concerned that people enjoyed them.

DD: The Reader covers a lot of delicate ground and I’m assuming that you had to be careful so that nothing was misread, no pun intended.

Hare: There’s never been a film of this subject before, a film about the effects of the crimes of World War II on the succeeding generation in Germany that was born after the war. They were not responsible for the crimes, but they live in its shadow and who have to make their lives as best they may and who have a whole series of complicated feelings about what has happened. So we knew we were broaching completely new ground. And as with all new ground, you have to make sure that it’s well-prepared.

DD: Writing an English language film based on a German novel and featuring a German point of view had to be a challenge.

Hare: It’s funny–[The Reader novelist] Bernhard Schlink and I have talked about this. Actually, I was born in 1947 and I was aware that much the most important thing that would ever happen in my life happened before I was born. We were all living in the shadow of this event, which somehow I had missed. Of course, British history, the war has a very different color, a heroic color. It was Britain’s finest hour. When Bernhard and I were discussing post-war experience—one in Germany and one in Britain—we discovered that we had more points in common than you might expect. So I must say that I did not find it difficult to imagine what it was like for him.

DD: I think there would be general audiences out there who would read a synopsis of the film and think there would be some kind of redemption or absolution in the end.

DH: There isn’t. I neither wanted nor was I in a position to forgive Nazi war criminals. Stephen Daldry and I felt very, very strongly that as filmmakers, we have not suffered what the victims of Nazi war crimes suffered. We had absolutely no right to extend so-called forgiveness or redemption to Kate Winslet’s character—and nor does the book. And it’s historical fact that very few people who were involved in the killing machine, in that sense, repented. Most people, I’m afraid to say, who commit war crimes take it to their graves that they were justified or at least partly justified to have taken their actions. That did present some big problems for me as a screenwriter.

DD: I would imagine that knowing you were writing The Reader primarily for an English-speaking audience would make it difficult.

Hare: I would say that countries which have been occupied or which have suffered dictatorships, it would be much easier for them to understand the film. More so than countries which are innocent to dictatorships or occupations. People know that ordinary people get caught up in dictatorships. They’re used to the idea that in order to save your own skin, you find yourself doing terrible things. People in 1930s Germany were faced with a very severe choice—if you stuck your neck out against the regime, you would lose your life. And there were those who had the courage to do that—the willingness to lose their own lives.

Hare: I would say that countries which have been occupied or which have suffered dictatorships, it would be much easier for them to understand the film. More so than countries which are innocent to dictatorships or occupations. People know that ordinary people get caught up in dictatorships. They’re used to the idea that in order to save your own skin, you find yourself doing terrible things. People in 1930s Germany were faced with a very severe choice—if you stuck your neck out against the regime, you would lose your life. And there were those who had the courage to do that—the willingness to lose their own lives.

DD: As to the shooting of the film, were you on-set and an active part of the day-to-day production.

Hare: As far as I could bear it, yes. Stephen is a very collaborative director. If he had his way, he would have me there everyday, all day. But the problem for a screenwriter is that you’re desperately needed for two hours and you’re not needed at all for the other twelve.

DD: You’re a director also, though I don’t think you’ve directed a feature in a while.

Hare: It’s been an awfully long time since I’ve directed a movie and it’s true that I know a lot about filmmaking. Again, because Stephen is such a generous fellow, he likes having me around. He likes having everybody around. One of the reasons he’s so brilliant is because he’s not remotely touchy or defensive. He will listen to absolutely everybody’s point of view on the set. He’s the least touchy director I’ve ever worked with. He doesn’t have to pretend that he’s the auteur and that all the ideas come from him. It’s such a relief. But he is still completely in charge and it is his movie.

DD: I saw you onstage nearly a decade ago in Via Dolorosa and very much enjoyed watching you act! Are there any more acting roles in the future for you!

Hare: After Via Dolorosa, I was offered some. Recently, I met with the James Bond people about writing a James Bond film and I did say to them, ‘It’s very nice of you to ask me to write a James Bond film but I’d rather appear in it!’

Leave a Reply