Disc Dish was thrilled to chat with legendary Hungarian-born cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, whose life and career is chronicled in the engaging 2008 documentary No Subtitles Necessary: Laszlo and Vilmos (DVD

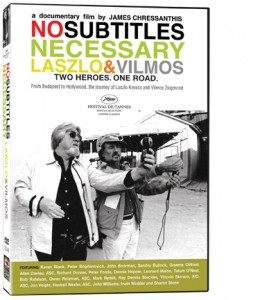

Disc Dish was thrilled to chat with legendary Hungarian-born cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, whose life and career is chronicled in the engaging 2008 documentary No Subtitles Necessary: Laszlo and Vilmos (DVD $19.95, Cinema Libre, release: Feb. 28, 2012).

The ‘Laszlo’ who shares billing with Vilmos is the late, great cinematographer László Kovács, Zsigmond’s lifelong friend and colleague who passed away in 2007. As No Subtitles Necessary reveals, fellow Hungarian László and Vilmos were film students in their native country. They fled their homeland together in 1956 when Soviet troops invaded to crush the Hungarian revolution. Eluding capture and fleeing Budapest with secretly shot footage of the Russian invasion in tow, the pair arrived in Los Angeles in the early 1960s, worked on a slew of low-budget independent movies and educational films, and began their rise to prominence as the decade came to a close.

By the 1970s, both László and Vilmos were considered to be among the finest artists in their cinematographic field. As that decade alone saw Zsigmond shooting such films as Close Encounters of the Third Kind, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Deer Hunter, Deliverance and The Long Goodbye, it’s clear that his elite status isn’t being exaggerated.

Disc Dish: No Subtitles Necessary director James Chressanthis, who was your assistant on the 1987 film The Witches of Eastwick, has wanted to make his movie about you and Mr. Kovács for more than 20 years What did you think of the idea of someone making a film about your life?

Vilmos Zsigmond: At the beginning, I didn’t like the idea too much. I don’t like to be in front of the camera—my place is behind the camera. But I had to do it in for László. It was coming close to the end; we knew it was going to be his last year and everyone wanted something on his life and our life together. ‘Let’s do it,’ I said. I’m glad now that we did it. It would have been a shame not to. It really is a great story.

Vilmos Zsigmond: At the beginning, I didn’t like the idea too much. I don’t like to be in front of the camera—my place is behind the camera. But I had to do it in for László. It was coming close to the end; we knew it was going to be his last year and everyone wanted something on his life and our life together. ‘Let’s do it,’ I said. I’m glad now that we did it. It would have been a shame not to. It really is a great story.

DD: What do you think Mr. Kovacs would have thought of all the technological advances of the last several years?

VZ: He would probably be in the same place as me, keeping up with the times. Over our careers in film, we always had to learn about new kinds of lighting, film stock and new technologies. He’d probably be doing the same thing that I was doing today. You can’t just stick with what you know, you have to evolve. There are a lot of good things about the new technologies, and a lot of bad things as well,

DD: Tell us about the bad.

VZ: I’m not really satisfied with the technology today. Using film was so much easier than the digital technology of today. But digital is still at the beginning of what it can be and they’ll be fixing all those problems. It’s just too complicated—negatives, tinting, flashing—it’s a whole new system that takes a lot of time. Of course, it’s not as physical. Even the editing. You used to feed a piece of celluloid into an editor. [Digital] is not expensive and that is an advantage, but I must say that I don’t love it. But it’s going to be fine in five years.

My first experience with digital filmmaking was The Maiden Danced to Death [which was shot several years ago and released in Europe in 2011]. It was a small Hungarian film about two brothers, and I wanted to do it because we were shooting in Budapest. I did it with a fellow Hungarian cinematographer, Zoltan Honti, a former assistant and an AFI student. He took over the film in the middle of the production because I had another commitment and I had to fly back and forth for post-production. But we did a good job of telling the story. It’s a nice little film.

DD: I’m not familiar with it.

VZ: I don’t think it has played in the U.S. It’s a small film that doesn’t have any stars. You make a film for a million dollars and then it costs $10 million to sell it. That’s the problem at the moment with independent filmmaking: You can make it cheap and then there’s no money to market it.

DD: Much has been written about your work on McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Close Encounters and your other landmark films, so I was hoping I could throw a handful of other titles at you and perhaps you could give us a story or two about them.

VZ: Very well.

DD: Let’s start with the comedy Jinxed from 1982.

VZ: It was great fun working with [director] Don Siegel, though he wasn’t well at the time. He had cancer and he would be sleeping a lot, even during the shooting. While we were lighting, he would go back to his trailer and sleep. One time, when we broke for lunch, he asked me how long it would take to light the next scene. I told him it would take an hour and he said, ‘I know, but take two hours.’ I told him I could try. So I got back from lunch and began setting up and I was really trying to do it as slow as possible. But I couldn’t do it that slow. It couldn’t take me more than an hour-and-a-half or an hour and forty-five minutes. When I was ready, they woke up Don and he came to the set and he started yelling at me, ‘You said it was going to take two hours!’

Another funny story is when we did a scene with Don and [leading lady] Bette Midler and Don played the owner of a sex shop. Bette is going to enter from the right and cross left and Don is coming in from the left and crossing right. And I remind Don that Bette cannot be photographed from her right—she didn’t wanted to be photographed from the right side. And Don says he doesn’t care, he’s not going to change it. And I tried again and he said, ‘It’s not about her—this is about me! I’m the star of this scene and my left side is better, too.’

After a while, we were all laughing at the whole thing. But it’s great to work with Bette—she can do everything. And she really didn’t care what side I shot her on because she knew I would do the best job I could.

DD: How about Brian De Palma’s The Bonfire of the Vanities from 1990?

VZ: Brian De Palma (Blow Out) really knows what he’s doing with the camera. He does incredible 360-degree shots, beautiful set-ups, long takes. He’s really great at planning out shots. In Bonfire of the Vanities, the five-minute Steadicam shot opens the film. The shot comes up from the garage and basement, into the elevator, then down the hallway, across the floor and into a ballroom with 800 people sitting there. Brilliant. He knows how to tell a story with one shot.

Telling the story with only a few shots, I love that style. It makes you feel like you’re part of the action, part of the story. It reminds me of the theater, where one act is basically like one long shot. It almost makes you forget that you’re seeing a movie. Those kinds of shots involve movement and lighting—where you’re moving about and going from one room to another. And they draw you into the story completely.

DD: But those magnificent shots do draw attention to the technology, to the fact that I’m watching a movie. I find myself getting drawn in, yes, but I’m also aware of the work that’s going into the shot, particularly if it’s a long and complicated one. I don’t know if I could forget that I’m watching a movie.

VZ: These days, I think it draws attention because it imitates other movies. Sometimes the shots serve as homages to other movies and other directors, like Hitchcock. There are many, many different kinds of movies and directors and styles. I don’t mind that a movie looks like a movie.

DD: How about Melinda and Melinda from 2004, your first of three collaborations with Woody Allen (Midnight in Paris)?

VZ: I had never met Woody Allen before Melinda and Melinda. My agent knew the producer of the movie and he suggested that we would work well together and then we did. We had a great time on that film and [2007’s Cassandra’s Dream and 2010’s You Will Meet A Tall Dark Stranger].

I love Woody Allen. He’s very clever, always thinking, and he’s great with actors. He lets actors do what they want to do and occasionally he’ll give them a specific kind of direction. He’s not really a technician when it comes to cameras and photography; I don’t know if he even knows the difference between lenses. He’ll just say give me a close-up or a wider shot and then maybe he’ll look through the lens and say that it’s fine or that maybe we can make it wider or tighter or something like that. He actually lets a cinematographer do his job. We like filmmakers who let us do our job.

DD: Sean Penn’s (Fair Game) 1995 film The Crossing Guard?

VZ: As an actor, Sean is brilliant. And he’s really an excellent director, as well. We got along really well. We worked out camera placement together, we never fought and he let me do my thing. I think we told the story the best way. And he’s very good with actors, of course, and in this case it was Jack Nicholson (Five Easy Pieces).

DD: Now would be a good time ask about The Two Jakes, the 1990 sequel to Chinatown directed by Nicholson.

VZ: Jack really knows about the camera. He’s one of the directors who likes to play with the camera. He’ll change things around, play with lighting, things like that. He’ll even spend hours on the set-up for an insert shot. He’s an interested person who gets involved in all the aspects of the films he is making.

There’s a scene in The Two Jakes that takes place in a trailer. We’re inside of this trailer and the only lighting is from a street light outside that’s coming in through an opening in the curtains. Jack is the only one entering the trailer in the scene, by himself, and I actually lit him with the light coming through the opening in the curtains. So Jack had to hit this one mark or nobody would see him. I didn’t tell him about it–a lot of actors don‘t like being told about marks. I was praying that he would hit the mark. So we did the scene eight or nine times and every time, he hit the mark perfectly. Every single time.

Afterwords, Jack comes up to me and smiles and says, ‘Well Vilmos, did I hit your lighting mark?’ He knew everything I was doing all the time.

DD: I’m not a cinematographer, but I do know that it’s all about actors hitting their marks!

VZ: Sterling Hayden (The Killing) was a guy who was always afraid of his marks. [Director Robert] Altman told me about Hayden when we were making The Long Goodbye — that he was afraid that having to be aware of his marks would take away from what he was doing, from his confidence. When I learned that, I started to barricade his choices for movement on the set. I didn’t want him going in any direction he wanted, so I limited his movements. I re-arranged furniture, the desks and the chairs, so he had no choice but to hit the marks that were left for him.

At the end, Hayden told me that he was thrilled about the way he moved around the set, that wherever he would go, there would be lighting. He didn’t think about his marks because they were set in the only places he could move.

DD: A brilliant strategy. Okay, how about the 2001 television movie The Mists of Avalon?

VZ: The Mists of Avalon was a big project and I liked the director [Uli Edel]. With television, it’s difficult to do some things. You have to shoot so many minutes a day, so you always have to be prepared or you won’t be able to complete the number of pages that you have scheduled for that day.

But we had a great time on that shoot and we were on wonderful locations in the Czech Republic. Mists was a period piece and those are really great to do. In a period piece, particularly a fantasy, the lighting is your own choice, the lenses are your own choice. It’s really a great thing for a cinematographer to do. Everything is open for you. You can even be more creative and you can use more shadows than usual. I like to say that lighting is about taking the light away. I often like to use the shadows more than the light.

DD: Can you tell us what any of your future projects might be?

VZ: There are a few possibilities. There is a TV pilot, or possibly a low-budget movie with a four-week shoot that we can shoot in Canada. There’s another project, one with a very long schedule, that I might shoot in Hungary. I can’t really talk about them officially yet.

DD: Wow, that’s a lengthy list of possibilities! I thought you might be on the verge of retiring after more than half a century of amazing work.

VZ: I am actually retired — yes, I am retired. But I like to work. So I’m retired until someone calls me up to work.

|

Buy or Rent No Subtitles Necessary: Laszlo & Vilmos

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

DVD |

|

DVD DVD |

|

Absolutely fabulous interview – I think that McCabe and Mrs Miller is one of the movie greats in so many ways including Leonard Cohen’s music and the amazing imagery of the locations and sets. It is great to be able to hear the thinking (and the wit) of one of the prime movers in the cinematography field. Many thanks.

Terrifiic interview with one of the greats. I am happy to hear baout The Long Goodbye, one of my favorites.