STUDIO: Kino Lorber | DIRECTOR: Josef von Sternberg | CAST: Akemi Negishi, Tadashi Suganuma, Kisaburo Sawamura, Shoji Nakayama, Jun Fujikawa

RELEASE DATE: 4/25/17 | PRICE: DVD $17.99, Blu-ray $20.43

BONUSES: newsreel footage, comparison between ’53 and ’58 versions of the films, deleted scenes, visual essay by Tag Gallagher, interview with Nicholas von Sternberg

SPECS: PG | 91 min. | Drama | 1.37:1 fullscreen | mono | In Japanese and English

Josef von Sternberg is often spoken about as a master of “exoticism.” His films did take place in gorgeous, exotic locales, but these settings were also thoroughly artificial. Sternberg’s China, his Spain, his Russia, are all impressions of the real places, filtered through the filmmaker’s unerring sense of eye-catching design.

Anatahan (1953), his last feature, was his most extreme experiment in telling a tale set in an exotic locale. To make the film he traveled to Japan, where he could ensure authenticity — and then, true to his wonderfully immersive (and wonderfully eccentric) style, he chose to recreate his slice of Japanese life inside a studio, crafting a jungle paradise that existed inside his own mind.

Through inspired by real events, the film is a blissfully fictitious tale of Japanese sailors who are shipwrecked on an island during WWII and discover a man and his “wife” — a woman (Akemi Negishi) who becomes for them in the several years that they then spend on the island “the last woman on Earth.”

Sternberg wrote and directed the film as an allegory about civilized men sinking to a “savage” state in a primitive setting. While he wanted the picture to be thoroughly Japanese, he also kept it “foreign” enough in nature so that it could be occurring at any time in history among any group of men.

The male characters are given specific personalities, but they still function as one big group, while the sole woman on the island acquires a personality and, much like the characters played by Marlene Dietrich in earlier Sternberg films, is the only person you can vividly remember by the time the film is over.

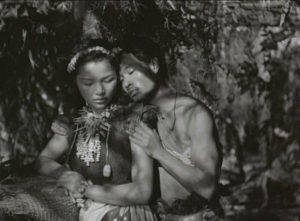

“Queen Bee” Keiko (Akemi Negishi) with one of her numerous suitors in Josef von Sternberg’s Anatahan

The main “alienation effect” that Sternberg used to underscore the film’s “foreign” nature was to have the actors speak in Japanese throughout, with a narrator (Sternberg himself) telling us what they’re saying. The result creates a distance between the viewer and the film, and definitely reinforces Sternberg’s role as a storyteller, offering us a “fable” that could pertain to any culture but our own (unless, of course, you understand Japanese).

The other effect of this technique is to basically make Anatahan a silent film. Spoken in the voice of one of the sailors (who’s never identified), Sternberg’s narration serves the same function as intertitles in a silent film — to situate the action and offer some semblance of an “authorial” voice, but never to allow the dialogue to assume any real importance.

The film has been available in different states over the years, but this package offers an impeccable restoration of Sternberg’s 1958 re-edit of the picture. A supplement included here shows the difference between the ’53 and ’58 versions of the picture. The shot order is rearranged in certain scenes, but the primary addition was a number of shots of Negishi in the nude. These images are jarring in the film because the male characters are nearly always seen in the jungle studio set, whereas Negishi is allowed to “escape” to the rocks on the coast of the island, where she sunbathes and eventually does escape with the help of unseen outsiders.

Another supplement, a section of unused footage, contains more images of Negishi in the nude, including a scene where she is seen flagging down airplanes by waving at the skies while naked.

A visual essay by the historian Tag Gallagher offers the occasional colorfully phrased rumination (“So, is there no free will, no morality [other] than guns and cocks?”). Gallagher does offer enlightening info about the ways that Sternberg transformed the original news story about the shipwrecked Japanese sailors (which is also viewed on the disc, via newsreel footage). He halved the number of the soldiers and transformed the one woman into a special object of desire.

The supplement that provides the most info about Sternberg and his dedication to the film is an interview with his son, Nicholas von Sternberg. He tells us how his father sold off a good chunk of his highly valued art collection in order to co-finance the film with a group of Japanese producers. Sternberg was resolutely anti-war, according to Nicholas, and Anatahan was “his most personal film.”

As for the most unusual aspect of the shoot — his father directing a cast whose language he couldn’t speak — Nicholas displays an amazing artifact, his father’s film “chart” to be shown to the actors. On it he mapped out the plot, indicated which emotions (color-coded, with Japanese translations) were needed in each scene and how the ensemble would intersect with each other throughout the film.

Sternberg was always very deeply involved with the production design of his pictures. His son reveals that, in addition to personally shooting the film and assembling the chart, Sternberg designed the sets and personally painted various elements to make them register better in black and white. Thus, while Anatahan is certainly not a home movie by any means, it was “signed” by its auteur in several ways.

|

Buy or Rent Anatahan

|

|---|

Leave a Reply