STUDIO: Arrow | DIRECTORS: Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin | CAST: Anne Wiazemsky, Juliet Berto, Gian Maria Volontè, Cristiana Tullio-Altan

RELEASE DATE: 2/27/18 | PRICE: Blu-ray/DVD Combo $62.89

BONUSES: “A conversation with JLG” full-length interview with Godard, analysis of the films by film historian Michael Witt, 100-page booklet including writings by, and interviews with, Godard and Gorin

SPECS: NR | 456 min. | Drama/Documentary | 1.37:1 widescreen | stereo | French with English subtitles

For just about a half century, Jean-Luc Godard (Weekend, Breathless, La Chinoise) has been a cinematic master who has provoked (and openly annoyed) some viewers as much as he has enriched others. The most obscure period of his career is the decade (1969-1979) in which he concentrated almost entirely on producing challenging, complex and, most importantly, wholly sincere, political “essay” films.

The first three years of that decade found him making indelibly Marxist films with various colleagues who loosely comprised “the Dziga-Vertov group,” a filmmaking collective that was led by Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin (now a noted film professor in the U.S.). The films from this three-year period have much in common with Godard’s more crowd-pleasing films of the Sixties and his personal films and videos of the Nineties and 2000s, but they have never been available in decent prints in the U.S. until now, with the release of Jean-Luc Godard + Jean-Pierre Gorin: Five Films, 1968-1971.

The films were a rupture in Godard’s career — not just because he was leaving behind fictional storylines, but because he was earnestly communicating his political beliefs. Just two years earlier, in Two or Three Things I Know About Her, he had whispered his narration for the film; from 1969-’71 he collaborated on films that in effect “shouted” the filmmakers’ beliefs with ardently Marxist narration, and dialogue and characters who were mouthpieces for certain beliefs.

This doctrinaire viewpoint is present in all five of the films in this collection. The visual brilliance found in these films is strictly in line, though, with his earlier landmark features. First, there is the imagery — the sort of colors, compositions and handmade collages that were present in films like Pierrot Le Fou (1965) and Weekend (1967) are a key component in these “militant” films, doing much to counteract the strident nature of the narration. Second, Godard continued to focus on his performers in remarkably evocative close-ups. Lastly, there is a sense of urgency that makes the films living, breathing documents of their era.

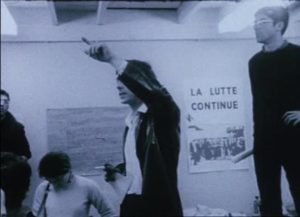

In terms of time capsules, there is none stronger than Godard’s self-financed Un Film Comme Les Autres (A film like the others, 1968), the first entry in this collection. It represents his full break from narrative cinema — gone is the subversive playfulness of Masculin-Feminin (1966) and La Chinoise (1967) — and remains a potent, if obliquely told, chronicle of May ’68 in Paris, the moment when the workers joined with the students in protest against the government.

The film continues Godard’s experiment with side and rear views of his subjects — we see three students and two workers in a field discuss the pros and cons of political action, intercut with original newsreel footage of the events of May ’68. Un Film is a work that purposefully “distances” viewers with the conversation scenes, but then stirs them up with the raw b&w newsreel images.

The second film, British Sounds (See You at Mao, 1968), is an examination of the working class in England that succeeds primarily because it is one of the sparest of Godard’s political films. We watch a production line assembling a car, a naked woman walking around her house and a mock broadcast of a right-wing TV host advocating that immigrants go back where they came from.

The sequences involving radical students and workers at the film’s end are more strained, as the students write political lyrics to Beatle songs and an all-male group of workers sits around in suits and ties talking about their struggles with management. The film’s images stay in the mind and defuse the “lecturing” voiceover.

The first film that was truly made by the group as a (semi-)functioning entity was Le Vent d’Est (Wind from the East, 1969). A fascinatingly odd creation, Vent starts out as some kind of spaghetti Western with a Marxist message and then wildly spins into entropy as the film’s “storyline” disappears and the crew debate among themselves on camera.

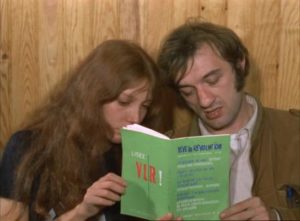

Vent was followed by the much smaller-in-scope Lotte in Italia (1970), which presents an Italian radical couple, with the focus on the woman (real-life film editor Cristiana Tullio-Altan) who analyzes her beliefs in both Marxism and feminism. She speaks in Italian and we hear her translated into French (and then, of course, we read her words in English).

In the meantime, Godard and Gorin discuss on the soundtrack the black screens that appear between the scenes and what they represent — complex things they couldn’t film or couldn’t afford to license from news organizations.

The last Dziga-Vertov group film is the most playful, the very curious Vladimir and Rosa (1971). Though filled with serious political platitudes, the film presents a screwball take on the then-topical trial of the Chicago Eight. Godard and Gorin and co. subtract most of the real-life defendants in the trial (the names Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin are heard exactly once in the whole film), and add in French workers and radicals, as well as the two actresses most identified with Godard’s career, post-Anna Karina: Juliette Berto and Anne Wiazemsky (his second wife).

Vladimir is crammed with information, opinion, and yes, dogma, but it also contains several memorably composed images and great set-pieces. The best of these finds co-directors JLG and JPG dressed as an American cop and a judge; the pair also appear (in their roles as “Vladimir Lenin” and “Karl Rosa”) as filmmaker/reporters who don’t quite know how their equipment works (and speak with silly voices one assumes are their versions of an American accent).

The set contains an invaluable booklet with several statements on the films by Godard and Gorin. The British film historian Michael Witt supplies an incisive and fascinating essay on the little-discussed topic of Godard’s place in the French Leftist press of the late Sixties.

Witt also speaks for 90 minutes in an onscreen supplement that contains a veritable treasure chest of behind-the-scenes info. He is uncommonly honest about the Dziga-Vertov group films, noting that Pravda (conveniently, the one D-V group film not included in the set, for unspecified reasons) provokes “the sense of being harangued” and that, watching the D-V group’s films, one feels one is “being told what to do.”

Aside from those completely valid criticisms, Witt covers the entire history of Godard’s “radical” period from 1967 to 1974, discussing several films not in the set. Along the way he discusses projects that Godard and Gorin initiated in Cuba, Canada, the U.S. and Palestine that were abandoned or were never started.

The most interesting revelations he imparts concern Vent and Lotte. He notes that the shoot of the former was chaotic, with different factions objecting to things Godard and Gorin planned to film. He also supplies the wonderful image of Godard handing out the producers’ money in cash to members of the crew — who reportedly bought a nightclub with the cash and chipped in on a Ferrari as well.

Lotte, he reveals, was the one D-V group film that was much more Gorin’s invention than Godard’s He further notes that the “Italian apartment” seen in the film is Godard’s own in Paris, and that, while the female lead was indeed an Italian activist, the male lead worked at a pizza restaurant downstairs from the apartment.

The pièce de résistance in the set is an incredibly revealing 128-minute (!) interview with Godard conducted in 2010, when he was 80. Two things are incredibly jarring: “Uncle Jean” (as he is known to diehard fans) is smiling and animated throughout, and he is willing to discuss his older films, something he has strictly avoided in many interviews.

The interview goes in several directions, with JLG discussing his latter-day work with video, his opinions on how cinema differs from the other arts and his thoughts on language. In the process, he reminisces with much fondness about the time he spent watching movies with his old New Wave comrades. He also speaks in depth about what he learned from his “cinematic uncles”: Rossellini, Antonioni and Nicholas Ray.

Along the way he indulges in his usual provocations, but this time with a broad grin. He trashes Avatar and other contemporary films, while also clearly attempting to piss off cinephiles by proclaiming that many commercials and modern films should switch places, with the commercials running two hours and the films running three minutes. He also maintains that he prefers watching dubbed foreign films to subtitled ones, since the subs take up valuable space on screen.

The most eye-opening parts of this far-ranging interview find him praising one of his older films at length (Weekend) and noting his affection for a few others (including Masculin-Feminin and Every Man for Himself). Of course, this chat can’t be all positive — he calls two of his well-loved Sixties films, A Married Woman and Band of Outsiders, a “waste of space.”

When asked by the interviewer what he would say to fans who revere Band, including Quentin Tarantino — who named his production company after the film — the ever-contrarian genius filmmaker responds that he would tell these fans that “it’s unfortunate for you… you chose the worst one!”

|

Buy or Rent Jean-Luc Godard + Jean-Pierre Gorin: Five Films, 1968-1971

|

|---|

Leave a Reply