STUDIO: Criterion | DIRECTOR: Pier Paolo Pasolini | CAST: Franco Citti, Anna Magnani, Ettore Garofalo, Orson Welles, Enrique Irazoqui, Totò, Ninetto Davoli, Silvana Mangano, Alida Valli, Terence Stamp, Massimo Girotti, Anne Wiazemsky, Pierre Clementi, Jean-Pierre Leaud, Maria Callas

RELEASE DATE: 6/27/23 | PRICE: Blu-ray $124.75

BONUSES: Two shorts made by Pasolini for anthology films; two documentaries made by Pasolini during his travels; new featurette on Pasolini’s visual style as told through his personal writing, narrated by actor Tilda Swinton and writer Rachel Kushner; audio commentaries on Accattone and Teorema; documentaries on Pasolini’s life and career; 1966 French television documentary; interviews with filmmakers and scholars

SPECS: NR | 951 min. | Foreign language drama/documentary | 1:37/1.85 | monaural

A one-man artistic movement, Pier Paolo Pasolini remains one of the most unique and significant figures to emerge in late 20th-century culture. In his native Italy he was well-known as a poet, a novelist, an essayist, and that rarest of phrases to be found in 21st-century life, “a public intellectual”; internationally he was and is best known as a filmmaker who, in a mere dozen features and a few shorts, created an indelible body of work.

The box set Pasolini 101, titled to both acknowledge the 101th anniversary of the artist’s birth and to “explain” his genius, represents the first time that seven of Pasolini’s features have been available in the U.S. in pristine shape on disc. (Supplanting the Water Bearer collections of a half-dozen of the films, from film prints, and an inferior release of Medea from Vanguard.) The other two titles in the box have already been released by Criterion (Mamma Roma and Teorema).

Pasolini’s remaining four features are out on Criterion in the Trilogy of Life box and the well-supplemented release of Salo, his last film. The design of Pasolini 101 is eye-catching and stylish, with only one small drawback — the discs are so tightly held in their respective paper pockets that one has to virtually riddle each disc with fingerprints to get them out of said pockets. (Note to binge viewers: Keep a microfiber towel close at hand.)

Several of Pasolini’s features shocked and outraged viewers when they were first released. The shock is now gone (except to very devout religious viewers and sexual Puritans), but one can’t fail to be moved by the deep emotion found in his films. There’s also a clear sense of maturation found when one watches the films back to back and sees how PPP became comfortable enough as a filmmaker to forsake the Neorealist mode found in his first two features to embrace abstraction and allegory.

It is often said of artists who die young that one can sense an urgency in their work, as if they were rushing toward something they needed to convey. That is the case with the films here, as Pasolini changed his style several times in the Sixties but never changed his tone or his essential messages.

The first two films, Accattone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962), are made in the style of Neorealists but (as was also the case with Bertolucci’s 1962 debut La Commare Secca, based on a story by Pasolini) they also reflect the innovations of the French New Wave and Pasolini’s own background as an author of poetry and fiction. His third film is the only non-essential picture by PPP, a documentary called Love Meetings (1964), about Italians’ views on matters of love, sex and tradition, which could be seen as Pasolini tipping his hand, providing his own reflections on the issues in the way he edited the material.

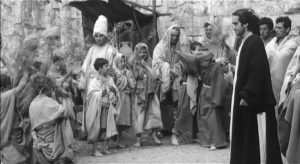

His fourth film is the beautifully transcendent The Gospel According to Matthew (1964), in which Pasolini presents the humble Christ, seen not as a majestic figure but as a common man touched by grace and compassion. Pasolini mixes anachronistic and historically inaccurate (but aesthetically consistent) elements, such as Odetta’s “Motherless Child” being included on the soundtrack.

The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966), Pasolini’s fifth film, is his only comedy, where allegory and metaphor infiltrate what looks to be a farce about two innocents (the immensely popular Italian movie comedian Totò and Pasolini’s friend and frequent star Ninetto Davoli) on a journey.

With his sixth film he turned to adapting the classics in his own innovative, stylized way. Oedipus Rex (1967) is his reworking of Sophocles’ tragedy to include details of his own life (conveyed in a frame device set in the 20th century) and use poetic but often not historically accurate costumes as part of a very personal aesthetic. He continued this in the final film included here, Medea (1969), the only feature film that found Maria Callas tackling a non-singing role.

In between Oedipus and Medea were his two most “Sixties” creations, the “absence of God” allegory Teorema (1968) and the brutal satire of industrialization and man’s impulse to (literally) devour his fellow man, Porcile (aka “Pigsty,” 1969).

Quantum leaps can be seen in these films, from one to the next. Where Accattone was shot in a flat, realistic fashion, Gospel is elaborately and innately visual. Hawks and Sparrows seems like a trifle, but it’s an intricately worked-out odyssey.

The films based on classics find Pasolini conforming the original works to his style and tone; the allegories are both easy to comprehend (although Porcile is delightfully overwrought) and compelling, with Teorema standing as perhaps his most profound statement on the deep-seated human need to believe in divinity and the tension that ensues when that divine creature exits one’s life. From first film to the last included here, one sees Pasolini growing as a filmmaker and as an artist, moving from depicting familiar milieus (people on the margins, focusing on criminals and families) to creating his own filmic universe and blending every element — locations, costumes, casting, music — to convey his messages.

The assortment of supplements included here explore Pasolini and his work from a number of angles. James Quandt does a splendid job of summarizing the many contradictions found in the man’s life and work in the 100-page booklet that comes with the set. Pasolini was indeed a man of many contradictions — among them the fact that he was clearly a subversive figure as a gay Marxist poet and pundit, but that he did not approve of the counterculture that developed in the 1960s.

Since Mamma Roma and Teorema have been out on Criterion for some time, the supplements provided for those films won’t be discussed here. The visual materials found for the seven films that are new to Criterion are a potpourri of interviews with PPP and his collaborators, as well as a few shorts that he made in the period covered by this box (1961-69).

The two shorts Pasolini made for anthology films are delightful. “The Sequence of the Paper Flower” (1969) is the most “hippie-fied” thing PPP ever made, with his favorite performer and friend Ninetto Davoli walking down Roman streets with the titular offering. The other short, “La Riccota” (1963), stars Orson Welles (speaking Italian but still dubbed) playing a director who is shooting a film about Christ that consists of tableaux from famous paintings. A highlight of the film, which was quite controversial thanks to its “irreverent” stagings of Christian iconography, has Welles (whose dulcet tones are sorely missed here) reciting a poem by Pasolini about the juxtaposition of the ancient with the modern.

The lengthiest documentary included here is the 1966 French TV documentary “Pasolini, the Enraged” by Jean-Andre Fieschi. Pasolini speaks French through most of the documentary, struggling to find the correct words for his very precise thoughts. Several of his collaborators serve as talking heads. Totò admits he wasn’t sure what he was acting out in Hawks and the Sparrows; Franco Citti is on hand to deny the accusation that PPP would “abandon” the non-professional performers he cast in his films; and Pasolini assistant (and acolyte) Bernardo Bertolucci notes how seeing the writer-turned-filmmaker use filmic techniques for the first time on the set of Accattone was akin to seeing “the first traveling shot… the first close-up in the history of cinema.”

Pasolini himself speaks at length in the documentary about how his first two films were a “revolutionary evolution of Neorealism” and how he had focused on the “underclass” as an artist because he believed it reflected the “split nature” of Italy, which he felt was comprised of “Northern moralism and Southern apathy.” The most lively story he tells is about a time that he, Ninetto and Ninetto’s brothers were set upon by a group of fascists, whom they proceeded to fight with. (Pasolini may have been a man for whom the life of the mind was paramount, but he does seem pleased recounting how he successfully took on one young fascist with his fists.)

A second shorter French TV documentary by Fieschi called “Ninetto the Messenger” from 1997 revolves around a later interview with Davoli, who reflects back on the scene in “Enraged” in which he “interviewed” Pasolini (but wound up being interrogated about class culture by the artist). Fieschi avoids the often-discussed fact that Pasolini had a real-life infatuation with Davoli by having the actor (who began as yet a non-professional “type” that Pasolini saw among the extras who came to be in a film) talk about PPP as an intellectual who also loved to play soccer and hike with his friends, being a “vigorous kind of man.”

The obvious deep-seated affection that Davoli had for his late friend (the man who gave him a career as an actor) is reflected when Fieschi asks him to discuss how he was contacted when Pasolini was found dead. (He was beaten by a group of young men who might’ve merely been hoodlums or might well have been hired by PPP’s political enemies.) “I loved him more than my father,” Davoli squarely declares. He ate dinner with Pasolini on his final evening (discussed here) and was the one who identified the artist’s corpse for the police (not mentioned, out of obvious courtesy).

Various film-specific items are included as well. In a French TV interview conducted in 1969 for Porcile, Pasolini explains why he cast French actors in the leads (because the characters were petty bourgeois, a category he knew French performers could play well). He also discusses his opinions about rebellion as they are reflected in the film — that “total rebellion is a form of conformism” which ultimately leads nowhere.

A 2004 featurette about Medea includes interviews with the cast and crew. Production designer Dante Ferretti notes that paintings were Pasolini’s “focal point” for the look of the film, which was shot in sequence over a four-month period in Turkey, Syria, Pisa, Anzio and the Italian studio Cinecitta. Costume designer Piero Tosi notes that Maria Callas wanted no close-ups of her face but Pasolini broke this rule, feeling that close-ups were essential. Tosi also notes that Callas did her own stunts, at one point walking on fire, and fainted from wearing a costume that included many, many pounds of jewelry. (Tosi estimates it as “110 pounds,” but that sounds like a bit of hyperbole.)

A short French TV interview from 1969 with Callas finds her broadly smiling and saying hopefully (since Medea was indeed her first non-singing role in a feature) that “it could bring me some very exciting opportunities.”

Pasolini’s own short documentary, “Scouting in Palestine,” shows him searching for locations for Gospel in Israel and Jordan. Pasolini narrates the footage that was shot in those countries, noting his fascination with the countries and their inhabitants, but also registering that these locations were “totally unusable for our film.” He thus felt “disrespectful” on occasion just taking a sight-seeing jaunt where he would stop and talk to the locals on-camera. At times he interviews some of them, as at a kibbutz, which clearly aligned with his Marxist beliefs, or with the Jordanian children, whom he found to have a “savage, pre-Christian gentleness.” (A wonderfully poetic oxymoron.)

The half-hour short film “Notes for a Film on India” (1968) is the result of a trip that Pasolini took to India, during which he was mapping out the plot for a film to be set in the country. One can’t be sure if he ever intended to actually make the film (about a maharajah’s family that becomes impoverished after he sacrifices himself to some hungry tiger cubs). It most likely served as an interesting topic to discuss with his interview subjects, who range from very poor villagers and farmers to journalists and intellectuals. This short that shows that, even on vacation, PPP was constantly creating art.

Another short doc “Notes for a Critofilm” (1967) offers Pasolini in full verbal flourish, noting the main reason he took up filmmaking — to “leave language behind” (meaning verbal language, which had obsessed him since he composed poems in his mother’s dialect). “Through cinema I can mirror reality,” he states, noting that there are two kinds of films: the “prosaic,” where characters are the most important (for this type, he cites John Ford as the best example) and the “poetic,” which favors style (here he cites Godard). Perhaps the best quote in the interview is when PPP refers to cinema as “neither a technique nor a language, but a full-fledged tongue.”

The most comprehensive of the extras is the only one created for this set: a very informative 30-minute item called “Pasolini on Pasolini” in which Tilda Swinton and writer Rachel Kushner read quotes from PPP about the filmmaking experience, as related to the nine films in the set.

He notes that frescos by Giotto informed his Neorealist “street drama” Accattone and that he had great difficulty working with Anna Magnani in Mamma Roma, because her acting style included “something spurious” when contrasted with the non-professionals in the cast. As for Gospel, he noted that it presented a “double image” of both the legend of Jesus contrasted against the reality of the settings and non-professional cast. He also maintained that he shot Hawks in a “flat” style, to evoke the work of Chaplin.

As for his films in color, he deemed Oedipus “the most autobiographical” and spelled out which details in the film came from his own life. When speaking about his allegorical films he would be unabashedly straightforward, noting that the overall message of Teorema is “no matter what a bourgeois does, he fails,” and that film and Porcile are “poems in the form of a desperate cry.” When discussing Medea he explained that the past became a metaphor for the present as he developed the film.

As good as that original featurette is, this reviewer was most taken by one of the shortest supplements, a three-minute film segment featuring Pasolini walking in Times Square in 1966, shot by Agnes Varda. Pasolini answers questions pitched by Varda in his lyrical-intellectual fashion. He specifies that his films don’t include “Christian imagery,” that they instead contain recreated images from Italian painting. He also declares that “there’s no difference between reality and fiction,” with cinema existing “as an audio-visual reality, and dialogue is a part of reality, a part of the image.”

Varda got Pasolini to answer her questions on audio tape in 1967, and so we hear him talking about art and religion as we see vintage (crisply restored) 16mm color footage of him walking on the Deuce and elsewhere in that vicinity. (All of it punctuated by The Doors’ “The Changeling”!)

|

Buy or Rent Pasolini 101

on Blu-ray

|

|---|

Leave a Reply