STUDIO: Criterion | DIRECTOR: Pier Paolo Pasolini | CAST: Silvana Mangano, Terence Stamp, Massimo Girotti, Anne Wiazemsky, Laura Betti, Andrés José Cruz

RELEASE DATE: 2/18/20 | PRICE: DVD $21.99, Blu-ray $27.99

BONUSES: 1969 French intro by Pasolini, interview with author John David Rhodes, 2007 interview with Terence Stamp, audio commentary by historian Robert S.C. Gordon

SPECS: NR | 98 min. | Foreign language drama | 1.85:1 widescreen | mono | Italian with English subtitles

If you used to stay up late in the Nineties watching softcore sex movies on Cinemax, you’ve encountered the plot of Teorema (“Theorem”) — or least the first half of it. For Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1968 masterpiece has a premise that was stolen for several 1990s “soft” sex movies, but the makers of those film truncated the storyline in the middle, leaving out (for obvious reasons) the beautiful and quite profound “death of God” conclusion of Pasolini’s original.

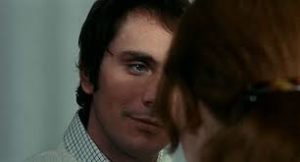

The film is arguably Pasolini’s best, thanks to its rigid structure and eloquent messages about faith and the price of sexual liberation. The premise referenced above is as simple as can be. A well-off bourgeois family in Milan is visited by a stranger (Terence Stamp, The Adjustment Bureau) who proceeds to seduce and emotionally bond with each member of that household — mother, father, son, daughter, even the maid.

Suddenly he is called away just as quickly as he arrived, leaving the family in a shambles, with each member undergoing a different sort of nervous breakdown. (The maid becomes a mystic who accomplishes saintly deeds in the most curious and fascinating twist in the picture.)

Pasolini’s later “Trilogy of Life” spawned a number of unofficial follow-ups by sleazy filmmakers, attempting to capitalize on his brilliant erotic adaptations of various masterworks in public domain. This infuriated the filmmaker, who wrote an essay renouncing his trilogy, since he wanted no connection with the similarly titled rip-off movies.

His tragic death in 1975 kept him from ever knowing about the straight-to-video films that emulated the “visitation” first half of Teorema, but one can readily assume the erudite polymath Pasolini (who was also a poet, novelist, essayist, songwriter, and painter) would not have approved of movies like Fred Olen Ray’s Friend of the Family (both Vols. 1 and 2!) and the Shannon Tweed vehicle A Woman Scorned….

The fact that these rip-offs exist indicates the elemental nature of Pasolini’s scripting — but it also, naturally, indicates that the softcore moviemakers wanted nothing to do with the second half of Teorema, in which the film pays off its viewers’ attention and beautifully reinforces the allegorical side of the plotline, as the family lose their minds because of the departure of the man who “liberated” them.

Pasolini preferred to work with non-professional actors, but in Teorema he assembled his first “all-pro” cast; he put non-actors in the smaller, briefly seen roles — including his mother as a townswoman witnessing the maid’s “miracles.” Perfectly cast as “the Guest,” Stamp has very little dialog, but his physical presence underscores the character’s “charitable” nature and his inscrutability. His performance here serves as a fascinating counterpoint to his turn as the self-indulgent, self-destructive movie star in Fellini’s 1968 short “Toby Dammit.”

The four actors who play the family do a terrific job of conveying their characters’ snobby, hermetically-sealed existences, and their later panic at losing their “savior.” Silvana Mangano (Conversation Piece) and Andrés José Cruz are quite good as the mother and son, but La Chinoise‘s Anne Wiazemsky (at the time married to and serving as muse for Godard) and former matinee idol Massimo Girotti, as the father and daughter, have the broader task of appearing smug and isolated and then utterly losing it in the picture’s second half.

Pasolini’s favorite actress, Laura Betti (later his legacy-keeper), incarnates the maid, who is as curious a character as the visitor. Not a bourgeois individual, she has the most unique fate (becoming a small-town saint), supplying the most curious and fascinating aspect of the film’s allegory (for which all interpretations are valid).

The other important contributors to the film are never seen — namely, those individuals who wrote the musical score. Pasolini crafts a beautiful blend of a 1964 jazz piece, “Tears for Dolphy” by Ted Curson, Mozart’s “Requiem,” and a low-key, non-intrusive score by that cornerstone of Italian cine-music, Ennio Morricone (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly).

The extras include an interview clip in which Pasolini offers an intentionally vague description of the film as “a parable… a mysterious theorem… about a bourgeois Milanese family.” He readily admits Stamp could either be a figure representing God or the Devil, and that the film’s plot is not resolved, but he proudly maintains that the picture “raises issues.”

The audio commentary by author Robert S.C. Gordon provides valuable information about the works of art seen and heard in the film, from Mozart’s “Requiem” to the poems of Rimbaud and the paintings of Francis Bacon. He contrasts the film with Pasolini’s novel of the film (which presents more of the voices of the characters) and declares the film is “part allegorical mystery play, part Greek tragedy, and part abstract report with a hypothesis about modernity.” Rhodes also discusses the film’s history and its place in Pasolini’s relatively small filmography (and rather large bibliography).

The most welcome extra is a half-hour 2007 interview with Stamp, who recounts some wonderful anecdotes about Teorema and his preceding film, “Toby Dammit” (included in the feature Spirits of the Dead). After letting us know he was a last-minute replacement in the latter — Peter O’Toole bailed and Fellini asked a London casting director for “the most decadent actors” that could be found (Stamp and James Fox were sent) — he compares Fellini (an open, friendly individual who was willing to discuss his process with the actors) with Pasolini (a quiet, dedicated artist who shot certain scenes secretly with his own Bell and Howell camera).

The most welcome extra is a half-hour 2007 interview with Stamp, who recounts some wonderful anecdotes about Teorema and his preceding film, “Toby Dammit” (included in the feature Spirits of the Dead). After letting us know he was a last-minute replacement in the latter — Peter O’Toole bailed and Fellini asked a London casting director for “the most decadent actors” that could be found (Stamp and James Fox were sent) — he compares Fellini (an open, friendly individual who was willing to discuss his process with the actors) with Pasolini (a quiet, dedicated artist who shot certain scenes secretly with his own Bell and Howell camera).

Stamp notes that Pasolini spoke to him once before the film began shooting and then never again. The filmmaker instead relayed instructions to Stamp through actress Laura Betti. Looking for some kind of instruction, Stamp asked Mangano to ferret out what Pasolini thought of the Guest character and was told that he was “a boy with a divine nature…”

He reveals that Pasolini had the actors speak English in front of the camera, so that he could later dub in finalized dialogue (of which there was a bare minimum). Stamp summarizes this as PPP “writing the film after it was shot.” For those who are interested, the finalized English language dub of the film is present in this package on another audio channel.

He also declares that his eagerness to be in the film was exploited by producer Franco Rossellini (nephew of Roberto). Stamp agreed to give up most of his “points” on the picture (which he accepted in lieu of a salary) when Rossellini told him privately that the production was running out of money and would have to be shut down. After the film was finished, Stamp learned that Rossellini and company sold the film for a decent amount of money to a supposed distributor (whom Stamp believes was a shell corporation for Rossellini and the other producers), ensuring that Stamp “never made a penny from the film.”

Stamp’s best anecdote concerns viewing the film in a London theater shortly after it came out. He notes that the audience laughed at one point where “the Guest” wanders off into a field to play with the Milanese family’s dog. The reason? “They thought I was going to shag the dog.”

|

Buy or Rent Teorama

|

|---|

Leave a Reply