STUDIO: Criterion Collection | DIRECTOR: Brett Morgen | CAST: David Bowie

RELEASE DATE: 9/26/23 | PRICE: 4K UHD/Blu-ray $27.99, Blu-ray $27.99

BONUSES: Audio commentary featuring Morgen; Q&A with Morgen, filmmaker Mark Romanek, and musician Mike Garson at the TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood; interview with rerecording mixers David Giammarco and Paul Massey; “Rock and Roll with Me” (Bowie live)

SPECS: NR | 134 mins | Documentary | 1.78:1 | Dolby Atmos

No single, standard-length documentary can sum up the many twists and turns of David Bowie’s life and career. In the case of Moonage Daydream, the first film project fully authorized by the Bowie Estate (and, most importantly, using Bowie’s own archival footage), a biographical study was not what was desired, nor was it what was delivered.

For Moonage is a feature-length montage of imagery and footage that attempts only to discuss certain subjects pertaining to Bowie’s work and a few connected ideas about his life. It is, in short, meant exclusively for those who are already familiar with Bowie and not at all a “101” that would serve to introduce him to those who are unfamiliar with his “mythology.”

In interviews, filmmaker Brett Morgen emphasized the avant-garde, sensory assault aspect of the film, but at base level it most resembles Eat That Question: Frank Zappa in His Own Words (2016), the rock-doc that offered the equivalent of a full-length interview with Zappa, assembled out of all the on-camera interviews that he did during his lifetime. Morgen distilled the Bowie interviews (both audio and video/film) so that its seems that David is “narrating” the film, but throughout (especially when the interviewer hits pay dirt and is asking great questions) we are aware that Bowie is answering questions posed by curious journalists.

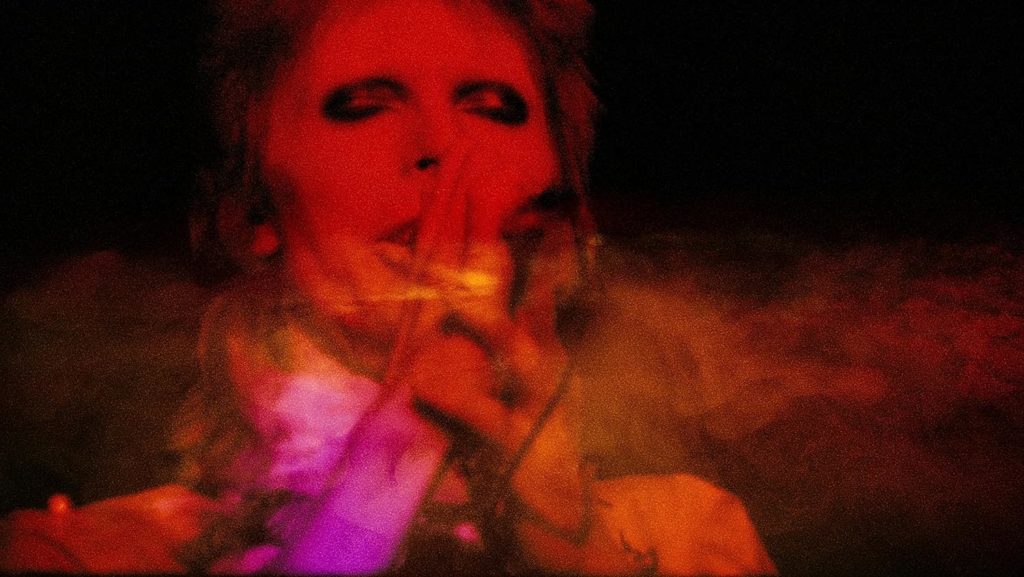

Moonage superimposes a carefully edited selection of Bowie clips on top of this “narration” along with the only newly created material, consisting of what Morgen calls “celestial shots.” (“Highly influenced and inspired by Tree of Life,” he notes in the audio commentary.) This combination of elements, made specifically with IMAX screens in mind, produces a “light show” effect, where Bowie the artist is shown at work (singing, acting, even painting), while we hear Bowie the philosopher and every so often the digitally enhanced archival footage moves forward in time.

Morgen credits himself as the “screenwriter” of the film — he notes that he began this aspect by creating a playlist of songs to be used in the film. This resulted in a curious chronology — in which a mid-’90s song (“Hallo Spaceboy”) and images from Bowie’s next to last video (“Blackstar”) bracket the film — which moves in a mostly chronological fashion, except when Morgen indulges in his own quick-cut music-videomaking (as when we see Bowie on many different tours dancing onstage while we hear a live version of “Let’s Dance”).

Morgen’s construction of the film as a series of avant-garde montages means that there are certain sources he borrows from quite often to craft his narrative. These include films that the diehard Bowie fan knows quite well — the Pennebaker Ziggy Stardust concert film, the U.K. TV doc “Cracked Actor,” Nicolas Roeg’s superb The Man Who Fell to Earth, etc. Morgen also indulges the Bowie fan’s penchant for wanting to see David in less familiar footage — here that desire is sated with many scenes taken from the 1983 doc Ricochet (in which Bowie is seen performing in and exploring Hong Kong, Bangkok and Singapore) and several never-seen concert films — the most impressive being a 1978 performance at Earls Court in London shot by David Hemmings (after Bowie appeared in his film Just a Gigolo) and intended to be a theatrical release, but shelved by Bowie.

The inclusion of the rarities underscores the fact that Moonage doesn’t function as an introduction to Bowie. (The trio of recent-vintage TV docs with “Five Years” in their titles serve that purpose.) Morgen not only does without talking heads of any kind, but he also dispensed with having onscreen titles (or album covers) to delineate the time period. This makes the film into a high-tech amusement park ride where one often gets glimpses of things one can’t fully digest. Witness two fast montages — one of paintings by artists Bowie admired and one of his personal pantheon of heroes; the paintings shown in quick succession can only be distinguished by the most keen fine-art fancier and the influences are also left unidentified, so that viewers can count themselves lucky if they can i.d. most of them.

Bowie cultists will also be aware of the many eras of his career that are missing here: his Anthony Newley “balladeer” phase; his stint as a long-haired singer-songwriter; his time as both as an “anonymous” piano-player in Iggy Pop’s band and as the lead singer of the Tin Machine; and most prominently the last two decades of his life (read: from 1997 to 2016), in which Bowie fused a very tight rock sound with his honed instincts as a songwriter. Morgen defends the omission of the last-mentioned in the bonus materials included here — as he felt that the equilibrium David found in his marriage to Iman was the real “conclusion” to the narrative. Thus, the sheer number of smaller journeys Bowie took are left out, in favor of a “major star” outlook (from Ziggy in the early ’70s to the grungy rebooted Bowie of the mid-Nineties).

Morgen speaks in the extras about the sensory connections he pursued in making the film — in which certain colors in certain performance clips match ones seen earlier, or where a sound/riff heard in one song was inserted at a very different moment. Thus, Moonage stands as a decidedly experimental film that has a great musical soundtrack as its main attraction while taking a trippy, unconventional look at its subject.

Morgen speaks in the extras about the sensory connections he pursued in making the film — in which certain colors in certain performance clips match ones seen earlier, or where a sound/riff heard in one song was inserted at a very different moment. Thus, Moonage stands as a decidedly experimental film that has a great musical soundtrack as its main attraction while taking a trippy, unconventional look at its subject.

The supplements offer information about the making of the film, as recounted by Morgen. The filmmaker is interviewed by director Mark Romanek (who directed two Bowie music-videos) onstage at the TCL Chinese Theater in L.A. Morgen recounts the details of a heart attack he suffered during the research process and how Romanek stepped in to be an insurance director, in case Morgen’s health troubles returned. Morgen declares that the project took on an added resonance after his heart attack, adding, “David saved me.”

In this interview Morgen talks about the choices he made for the film, including the outline of his prep work, which included two years in which he was allowed to watch every piece of video and film in the official Bowie archive. On an unrelated but certainly still Bowie-centric note, pianist Mike Garson discusses with Morgen and Romanek working with David, saying that he “never micromanaged” the musicians he worked with onstage or in the studio. Garson also offers the interesting detail that the album Outside (which is the last album included in Moonage) was the result of two weeks of improvisation that Bowie and co-producer Brian Eno did with the musicians.

Although diehard fans will no doubt wish there were many inclusions of rare Bowie material in the package, only one rarity is present — a live rendition from 1974 of “Rock and Roll With Me” on video. Audio-wise the clip is great, but it looks dismal, dark and washed-out in classic fifth-generation video dub fashion. One realizes watching it that it is seen in Moonage with digital improvements that both brighten the footage and “cover over” the imperfections with psychedelic distortions that make it at least look “cooler” in the long run.

The only original supplement in the package is a featurette on sound design in which we see scenes from the film while Morgen talks to sound mixers David Giammarco and Paul Massey. Morgen deems the film “an exercise in sound distribution” and notes that he chose many live sequences because they had 24-track sound and he needed that kind of sound density to go with the IMAX imagery.

Giammarco notes that the work done by himself and Massey on the live sequences “brings [the audience] closer to the stage than they’ve ever been at any concert” sonically, since various mixing approaches had to be used to make the music have a “fuller” sound than it had on much of the original footage they were working from.

The biggest “reveal” in this conversation is that, when a stadium concert scene needed mixing, various new sounds were recorded from scratch to be included in the mix. Sound designers John Warhurst and Nina Hartstone (who won Oscars for their work on Bohemian Rhapsody) rented out a soccer stadium in England and re-recorded some of the sound from different places in the stadium, so the music would be more appropriate when a long shot of the venue was seen onscreen. They also recorded original audience noises (including singing along with the Bowie songs) in that stadium, in order to give the audio track a vibrant feel during certain live sequences.

Morgen does a solo commentary for the film, establishing that he was helped by many technicians in crafting the film, but also that he wore many different hats on the production — his decision to assign himself several different credits brings to mind Marv Newland’s classic, credit-strewn “Bambi Meets Godzilla” cartoon. Most of the fans who will take the time to listen to this commentary will endure Morgen’s elegant phrasing (“Up to this moment, the film has been baked in mystery”) in hopes of “decoding” which clip in Moonage came from where.

We hear Morgen discuss the documentary Ricochet, which supplies much of the “where is that from?” footage in the film. The doc supplied Morgen with somewhat jarring images of the very white Bowie (in his dyed blond era) as he experienced modern culture in Asian cities (shopping malls) and remnants of the ancient (temples and religious ceremonies).

Morgen also provides details about the ’78 David Hemmings concert film that Bowie chose to shelve. He also points out when the single rarest items appear onscreen (briefly) — Bowie’s personal diary, notes for the Diamond Dogs tour and b&w experimental videos that the Thin White Duke created at his most L.A.-frenzied.

Aside from these notes, we do learn from the commentary about the restoration process and how certain clips took several days to present; Morgen estimates that the Hemming-shot version of “Heroes” took 80 hours of digital prep for it to appear as crisp as it does in Moonage.

Morgen frequently mentions that he could go in any direction he wanted on the film as there were no other producers. However, he reveals at one point that he initially wanted to make a four-hour film that would have an intermission but was told he had to have a running time in the vicinity of two hours. The other item imposed on him was that the film had to be released in theaters in IMAX. One assumes these requirements were dictates coming from the Bowie Estate (or perhaps an IMAX distributor?), but Morgen never clarifies matters on either point.

He cites the four themes he wanted to pursue in the film, namely transience, impermanence, chaos and fragmentation. Under the closing credits, he goes into detail about the heart attack he had while preparing the film and the way that hearing Bowie’s statements about life and death changed him. He declares Bowie to be a “paradigm of how to live one’s best life and how to make the most of our time on Earth.”

|

Buy or Rent Moonage Daydream

on 4K UHD/Blu-ray | Blu-ray

|

|---|

Leave a Reply